Wild Horses in Italy

Project by Elena Bajona and Elena Gagliani

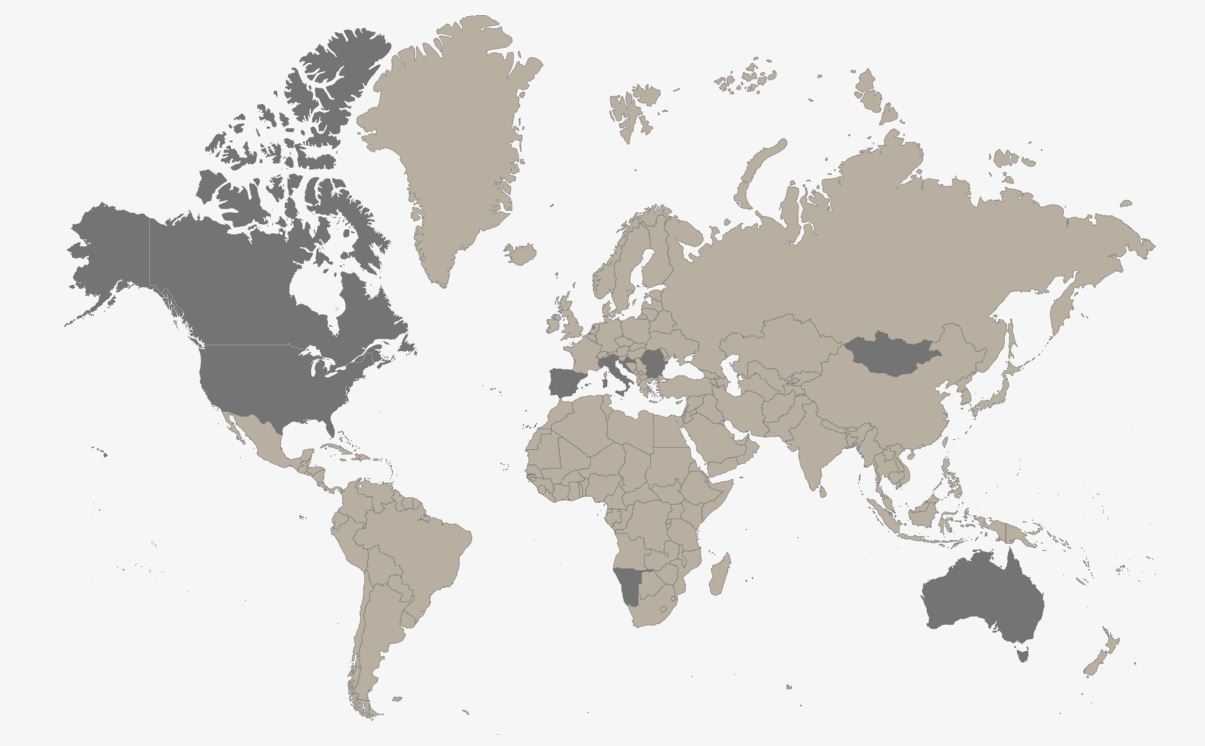

All our activities are regularly held in Europe, USA, Canada, Namibia, Mongolia

In 2010, the same founders of the project came upon a special place where they discovered some true wild horses in Italy, precisely in Liguria.

The site they explored offered a unique opportunity, as some of the census herds were really wild. Then it has been immediately organizing a group of students for the first activity of Wild Horse Watching in Italy which took place in October 2010. From this date on the Animantia Academy regularly carried out sessions with their students for observing the wild horses in Liguria.

In 2012 the project was sponsored by the WWF and the wild horse watching days also opened to the public.

The wild mustang roaming free in the great rangelands with a wind-swept mane has long been a powerful symbol of the American West, particularly in film and literature. Protected by Congress since the mid-20th century (western ranchers, claiming horses took valuable grazing resources away from cattle, began killing off the herds), wild horses of all breeds have a majestic beauty to them that makes them an attraction for animal and nature lovers.

Since 2004 we are conducting observation on these wild horses helping them to survive against the controversial human management since 1960.

Today, there are approximately 60,000 free-roaming horses in the United States and Canada combined. We encourage you to visit and observe North America’s wild horses with us. Here are some of the places we visit all year around to see wild horses:

- Private land in California

- On 2,000 acres of horse heaven located on California’s Central Coast, 72 wild horses and 16 burros roam free. Horses from the Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge in southeastern Oregon, along with other family bands, grace the beautiful rolling hills with a view of the ocean in the distance.

- On a 300 acre private wild horse sanctuary, diverse herds of the American Mustangs are living free. Horses who look as though they have literally stepped off the pages of a history book — such as descendants of Padres Kino’s Spanish Missionhorses, the Iberian Sorraia type Sulphur Springsherd and the rarely found Cerbat Spanish Mustang. Then, in the hills, are descendants of cavalry and ranch horses from the Great Basin and other rugged areas on Western Public lands. The sanctuary is also home to wild burros who live in the romantic oak forest.

- The Virginia Range, Nevada

- Nevada is home to nearly half of the nation’s free-roaming horse population. Many of those horses are part of the Virginia Range herd, which occupies a region in the western part of the state.

Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota

- The mustangis often used as a living and breathing symbol of the American West. That symbolism is on full display at the 70,467-acre Theodore Roosevelt National Park, home to 100-200 free-roaming horses, which can be seen grazing and galloping across the Dakota badlands.

The Pryor Mountains, Montana & Wyoming

- The Pryor Mountains are home to about 160 free-roaming horses, who mostly live in the northeast region of the mountains near Bighorn Canyon. Many of the horses display distinctive markings—a long dorsal stripe along the back and “zebra-like” coloration on their legs—and are smaller than the average wild horse.

Outer Banks, North Carolina

- There was a time when the wild horses of North Carolina’s Outer Banks numbered in the thousands, but the recent increase in popularity of this beach resort region has made a dramatic impact. Today, some fear that these horses (especiallythe Corolla herd, which has only 60 animals left) may not be around much longer.

Assateague Island, Virginia & Maryland

- The horses of Assateague first received worldwide attention thanks to Marguerite Henry’s 1947 Newbery Medal-winning bookMisty of Chincoteague. Beautiful and tough, these horses have since become immensely popular and attract tourists to the surrounding areas.

- While over 300 ponies wander the island in total, they are actually divided up into two different herds. TheMaryland horses, which roam the Assateague Island National Seashore, are looked after by the National Park Service. The Virginia horses, which graze at Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge,are cared for by the Chincoteague Volunteer Fire Company.

COME WITH US IN THOSE HORSE PARADISE

YOU WILL CONTRIBUTE TO PRESERVE THE AMERICAN MUSTANGS

Last wild horses in Africa

The Namib wild horses are arguably the only herd of feral horses left in Africa. The history of Namib Desert Feral Horses is quite unique and incredible. It is already a long time that the Animantia professionals disclose a documentary that presents their peculiar story.

One plausible theory relates to the German occupation of South West Africa a large number of horses were needed for the cavalry and an eccentric German nobleman, Baron Hans-Heinrich von Wolf, set up a horse breeding station at his outlandish castle, Duwisib, on the edge of the desert. Once Baron went off to the first world war in Europe nobody looked after the stable of more than 300 horses. Following his death, herds of his horses ran wild, roaming the veldt around Duwisib until 1950. It is possible that some of them wandered the 150 kilometers south- westward to the water at Garub.

It is likely, too, that some of the feral horses originated from the Schutztruppe mounts, as well as from the those belonging to a South African Expeditionary Force that took control of the Lüderitz- Keetmanshoop line during the First World War.

The conservation of the feral horses in the Namib-Naukluft Park has aroused controversy. Some people argue that the horses are of historical and scientific value and that they should not be removed. Many others think the horses, as non-native species, compete with the indigenous wildlife (mainly gemsbok, springbok and ostriches) for the sparse vegetation. In fact, there is little to no evidence of competition between the horses and the game animals, and the horses occasionally graze within a few meters of gemsbok and springbok without any apparent interaction. Gemsbok move away from the waterhole when horses approach and vice versa, but sometimes both species drink at the same time. Being relatively independent of water, the indigenous wildlife range over far greater territories than the horses do, so the presence of the horses has probably no significant bearing on the numbers of game in the park.

The Namib feral horses are unique in the sense that they have been isolated for a number of generations. Their hardiness in the face of extremely harsh climatic conditions is extraordinary, as is the fact that they have been able to circumvent the vital problem of food and water availability by adapting their behavior and their allocation of time. For these reasons, if for no other, they deserve our wonder and admiration!

The Takhi

In the Mongolian “Valley of the Wild Horses”—on the northern border of the Gobi B Nature Reserve, in a region called the Dzungarian Gobi, we can watch the takhi (meaning “spirit”), the only horse that was never domesticated, and still exists in its true genetic form, called also the Przewalski’s Horse or the Mongolian Wild Horse. Considered extinct at the end of the twentieth century, the small breeding herd that survived in captivity has since been reintroduced into its natural environment.

The Gobi B Nature Reserve is 12,000 square kilometers (about 4,600 square miles) of semi desert, a rocky plain bordered by mountains and interrupted by brush and rocky outcrops. Underground streams called “gobs” (which give the Gobi its name) feed springs that provide a periodic source of water, enough to sustain considerable biodiversity. Some springs function year-round, supporting narrow bands of pasture. Fields of saxaul, a woody shrub, provide food for the horses in the winter. During the summer the herds stay near a water source, but the moment the first snow comes, they’re completely independent.

Since 1997, takhi have been successfully breeding in the wild, though captive animals have deliberately been introduced to supplement the wild herds at Takhin Tal. As of winter 2007, 115 takhi were roaming free in the Dzungarian Gobi, including 76 animals born. These numbers are especially significant since computer models suggest that a group of 100 free-ranging horses is considered a viable population—one that is biologically resilient and less prone to natural catastrophes that could wipe out large numbers of takhi.

Today, all the Przewalski horses are descended from 9 of the 13 horses captured in 1945. These horses themselves are descended from approximately 15 horses that were captured around 1900. It’s an extreme population bottleneck, but somehow, populations grew as the wild horses refused to give up. It took more than 70 years and an international effort, but these wild horses are finally returning to their natural state in the wild, where they belong. It is worth it to visit them and breath their happiness.

CONTACT US FOR PERSONALIZED EXPERIENCES

The most remote wild horse colonies in North America – Sable Island, Nova Scotia, Canada

About 100 miles off the Nova Scotia coast lies the remote Sable Island that became famous because of the several hundred horses that roam this expansive sandy landscape.

While the exact origin of these horses is still a mystery, scientists theorize that they are descendants of horses seized by the British when they expelled the Acadians in the mid-18th century. Due to harsh conditions, many of the other animals died out. But the horses survived, roaming free along the sand dunes of Sable Island. Today, there is controversy around whether the horses should be allowed to stay there. While they are not native, there are arguments that both the ecosystem and horses have adapted to one another.

In 2013, Sable Island officially became a Canadian National Park, although the area isn’t particularly accessible—it can only be reached by plane or ship.